There is an interesting logic in the idea that putting hydrogen in the internal combustion engine (ice) can be a quick way to get clean trucks on the road – it reduces the construction of buildings, and creates the need for hydrogen nearby to increase the Refueling networks. It points to the urgency of everyone who participates in the supply of balanced hydrogen and releases the output.

But if the goal is Destainable deCarbonzation at a very low cost of living, physics and economics pull in a different direction. A non-essential difference is whether the technology is conventional or new; How many kilos of hydrogen are consumed to move a ton of goods per kilometer, what does that mean for operating costs and learning materials, and how does the solution help to tighten emission rules and expectations of spending money.

Fuel Cell setups convert chemical energy into electrical energy with much greater efficiency than a combustion engine. Conventional proton-exchange (PEM) fuel cell stack systems operate at stack efficiencies in the high tens to mid-fifties, and – when integrated into an electric drivetrain – benefit from regenerative regeneration losses and fewer mechanical losses. This results in materially lower hydrogen consumption in the same cycle.

Changes – or disruption?

It is common that the framework of hydrogen combustion as a pragmatic bridge: something to draw hydrogen is required by the time of production of cells and infrastructure infrastructure. However, it can provoke a serious risk – dynamic decisions that look economical in the short term can be a false economy and disruption if they delay effective investment.

In practice, early hydrogen demand driven by high-efficiency fuel-refining vehicles can distort market signals and Slow Cell Scale-Up. The infrastructure created for those vehicles is decidedly uneven, favoring volume over efficiency, while the investment in assembly lines and service networks becomes difficult to replicate.

Difficulty is expensive

Hardness and durability are the next considerations to consider. A combustion power plant, even one designed for hydrogen, inherits those of the legacy drivetrain: lubrication systems, high-temperature components, typenting machining hardware. This adds complexity – bringing more moving parts, more attention to hydrogen production (calling and life related to H2IC

Simplicity scale – fewer parts, fewer problems

In contrast, mobile gasoline engines are inherently simple as a subsystem: few moving parts,

Cost Trajectories are also important. Today, Fuel Cell Systems carry the largest cost (Capex) Premium Versus Mature Surrains of Diesel. But that premium is a function of scale, not physics – and the economics of the premium are real. Ballard's Fleet model shows that, with reasonable production assumptions and fuel cost degradation, Fuel Cell Solutions can reach convergence with H2ICE Alternatives in a few years. This crossover is driven by the continuous reduction in cell operating areas and the continuous sensitivity of the total cost of ownership (TCO) in fuel consumption.

There are also regulatory realities to consider. Fusion, even with pure hydrogen, produces species and particles that require post-treatment and may be subject to city and Corridor emissions regulations. The “True Zero-Tailpipe” certainty that comes with the electric cell makes it easier to plan for long-term compatibility and reduce the risk of damaged or unwanted goods as domestic policies and national policies evolve.

Practical Steps for a Resilience Solution

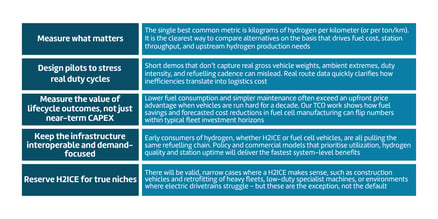

So where does this leave effective action? A few clear, non-ethical takeaways:

The transition to continuous learning: Systematic physics, economics and policy

The transition to stable cargo is complex and multidimensional: Technology selection, hydrogen supply, station economics and Fleet operations are all intertwined. My experience is that the best decisions come from aligning physics (efficiency), economics (fuel and utility costs), and coupon control (future demand). For many heavy-duty on-road applications that need to improve fuel consumption, control time, balance of benefits – low parts, low production method drissetrains – It points to Fuel Cell Electric drivetrains as an efficient way to emit zero.

We must use all the early adopters and learn to be quick with hydrogen supply logistics, economics at the station, and not to deceive the low kilograms of hydrogen that need to be sent, and which art uses that town the most? Cleaner, simpler, more efficient method has fallen miles.